Greetings from Yorkshire!

The thing about the Victorians, and it’s not said enough, is that they really knew what they were doing, at least when it came to codifying sports. I’ve just finished an extra-curricular activity which involved thinking, at least a little, about soccer’s origins, and whenever I do that, I’m reminded just how well conceived the whole thing happens to be.

I say happens because I cannot believe for a second that any of it was scientific, or academic, or even deliberate. The people who formalized soccer created a game that exists in a Goldilocks zone. Goals are sufficiently rare to be special, but not so rare that pursuing them is futile. The field is not too long, not too short: it is just the right size to reward both endurance and acceleration, but to make neither decisive. It is a technical game, and a tactical one, but in precisely the right measurements.

And the season: the season is a masterpiece. Short enough that every game matters, but long enough that one setback is not enough to unravel the whole tapestry. That is worth remembering. A week ago Liverpool was in crisis. A month ago, so was Manchester United.

Neither feels true now, but both might feel true again by Monday morning. There is a strange urge to make declarative, definitive judgments at the close of every round of games, at the end of every tranche of fixtures between international interludes. By hook or by crook, though, soccer is designed (sort of) to mitigate against both. The twists and the turns are a feature, not a bug.

The Makings of a Rivalry ❤️🩵

Whether it was the peak or the nadir of the feud that defined an era is probably a matter of personal taste. As Liverpool prepared to take to the field at the Etihad Stadium early in July 2020, Manchester City’s players lined up to welcome their opponent. Jürgen Klopp’s side had been confirmed as champion a couple of weeks previously. Tradition dictated they be granted a guard of honor for each of their remaining games.

I will admit to being a bit of a sucker for this stuff. There are, I know, plenty of fans who regard expressions of soccer’s sentimental side as (at best) hopelessly outdated and (at worst) saccharine to the point of nausea, but I quite like them. Fans applauding an opposing player for tearing their team to shreds? I find that stirring. Defeated supporters staying to watch a trophy lift? What sport should be. A guard of honor? A heartwarming display of professional respect.

That day, five years ago, it became clear that Bernardo Silva would be of a markedly different opinion. As Liverpool’s players walked, slightly smugly, onto the field, the City midfielder stood stony-faced and stock-still.

He did not clap. He could not clap. He had arranged things very carefully to preclude the possibility of even cursory applause. He had a cup of coffee in one hand and his shin pads in the other. The rest of his teammates performed their duty, even if it was a little begrudgingly. Silva mustered nothing more than blowing – theatrically – on his coffee.

Silva, presumably, knew it looked an awful lot like churlishness. A few years later, he would suggest that he saw the gesture as a form of “hypocrisy.” He explained that he did not need other people to clap for him when he had won something, so he had no intention of doing it for other people. That does not, admittedly, make it hypocritical, and nor does it mean that it is anything other than poor sportsmanship, but at least Silva’s refusal to bow to convention has the redeeming feature of being quite funny.

It was also fitting. For the five-year period between 2017 and 2022, the struggle between Liverpool and Manchester City defined the Premier League. They were, by some distance, the league’s two dominant forces. They were overseen not just by the two best managers of their generation – at least in England – but, in Klopp and Pep Guardiola, two figures who stood at the very cutting edge of the game. Both made a habit of racking up towering points totals, of tearing clear of everyone else. Their games were a test of strength, of nerve, of talent, but they were also battles of ideas.

The two coaches always seemed to recognize that. They rarely spoke about each other with anything less than respect; at times, it was even possible to discern not just mutual admiration, but genuine affection.

Klopp and Guardiola were strikingly different personalities: late in 2019, both appeared at a media dinner in Manchester. The German could not have been more at ease. The Catalan seemed a little less comfortable. In his speech, Klopp gushed at Guardiola’s dedication: he envied his obsessiveness, he said, his unyielding commitment to improvement. He would, Klopp said, love to have that quality. It was hard not to wonder if, perhaps, Guardiola might have felt the same about Klopp’s easy charm, his megawatt personality.

By and large, that respect permeated the players, too. Even Silva, in later years, would lavish praise on the challenge Liverpool posed to his side, although it’s probably worth pointing out that he did so only in the context of criticizing Arsenal, the team that inherited Liverpool’s status as pretenders to City’s crown. It may not, in truth, have been the most sincere praise.

But on every other level, the rivalry was undeniably petty. Liverpool fans threw objects at Manchester City’s bus before a game at Anfield. On the plane back from winning the Champions League in Istanbul, City’s players sang a fairly obviously inappropriate chant about Liverpool, and nobody seemed especially worried about apologizing when the footage emerged. At Premier League meetings, relationships between executives were frosty. At the peak, embarrassing stories about Liverpool appeared in certain British newspapers with rather greater regularity than had previously been the case. But maybe that was unrelated.

It felt, at the time, as though the enmity between City and Liverpool was the engine that drove interest – both domestic and international – in the Premier League.

The sheer quality of at least some of their encounters, the sense that at times they may well have been the best two teams in the world, meant it was possible to believe it might one day eclipse Liverpool against Manchester United as the biggest game in English football.

It might not have had the history of that game, of course, but it seemed to have something much more pressing at stake: Liverpool against Manchester City was the old against the new, then against now, history against future, tradition against ambition. Liverpool saw City as overnight arrivistes, lottery winners. In City’s eyes, Liverpool stood for the ossified and patronising establishment, the gatekeepers they planned to overturn. Again, the truth of that is a matter of taste. But it was good material for a rivalry.

It is striking, then, how comparatively low-key this weekend’s meeting between the two feels. They are second and third in the Premier League. They are the last two champions of England. They are the teams that have claimed every title since 2017, and featured in five Champions League finals for good measure. Both sides have changed considerably in the last couple of seasons, but many of the players who will take to the field on Sunday carry with them the scars of those battles.

That this should feel like a decaffeinated version might be attributed to the fact that both are straining to keep pace with Arsenal this season; this is not, like those truly classic encounters, a meeting of two great forces. Both have felt a little diminished this season, as though they are works in progress, although on current form that description applies to Liverpool more than City.

But just as relevant, I think, is the fact that a rivalry is not the same as a feud. The fans of City and Liverpool may not like each other. The executives may maintain a mutual distrust. But their animosity was inherently circumstantial, rooted in a direct competition for honors. That can be petty and it can be potent, but it is not permanent. The game’s great enduring conflicts are all rooted in something that Liverpool and City cannot possess, not yet: time. Genuine antipathy is not something that can be conjured. It needs to curdle. And that, just a little ironically, requires history.

📬 Enjoying The Correspondent? Check Out Our Other MiB Newsletters:

🐦⬛ The Raven: Our Monday and Friday newsletter where we preview the biggest matches around the world (and tell you where/how to watch them) and recap our favorite football moments from the weekend.

☀️ The Women’s Game: Everything you need to know about women’s soccer, sent straight to your inbox each week.

🇺🇸 USMNT Only: Your weekly update on the most important topics in the U.S. men’s game, all leading up to next year’s World Cup.

Good for Bayern, Bad for Europe 🇩🇪

Maybe the seventh time can be a charm. The summer of 2024 was a disheartening one for Bayern Munich. Deposed as German champion by Bayer Leverkusen, the club’s plan had been to reassert its dominance by coaxing Xabi Alonso – the mastermind of Leverkusen’s success – south, to Bavaria. It was a vintage Bayern move. If they might beat you, hire them.

Alonso, though, said no. So did Julian Nagelsmann, the Germany coach, when offered the chance to return. And Thomas Tuchel. Bayern promised Ralf Rangnick free rein to modernize the club. He preferred to stay with Austria. Oliver Glasner could not be lured from Crystal Palace. Estimates as to how many managers spurned Bayern’s advances vary, but it was somewhere between five and eight. In the end, they had to make do with Vincent Kompany, who had just overseen Burnley’s glorious relegation from the Premier League.

There is no point pretending it was anything other than an inauspicious start for the Belgian. Even claiming the Bundesliga title in his first season did not dispel the doubts. Bayern, after all, should win the Bundesliga. It has far more money, and far better players, than everyone else. It was not necessarily the case that Kompany had anything very much to do with it.

This season, though, has been different. Bayern’s win against PSG, the reigning European champion, on Tuesday evening was not just a statement of intent about Kompany’s side’s ambitions this season. It was also Bayern’s 16th straight victory in all competitions, a start to a campaign unprecedented in Europe’s so-called big five leagues.

This is not, to be clear, a sign that German – or even European – soccer is bursting with good health. Records like this fall with alarming regularity these days, a sign of just how lopsided much of the game has become. But it is a compelling indication that, as Bayern suspected, Kompany had the attributes to coach at the highest level, that the way his Burnley team played was a better guide as to his talent than the results it achieved. All of that rejection, 18 months ago, may yet have been worth it.

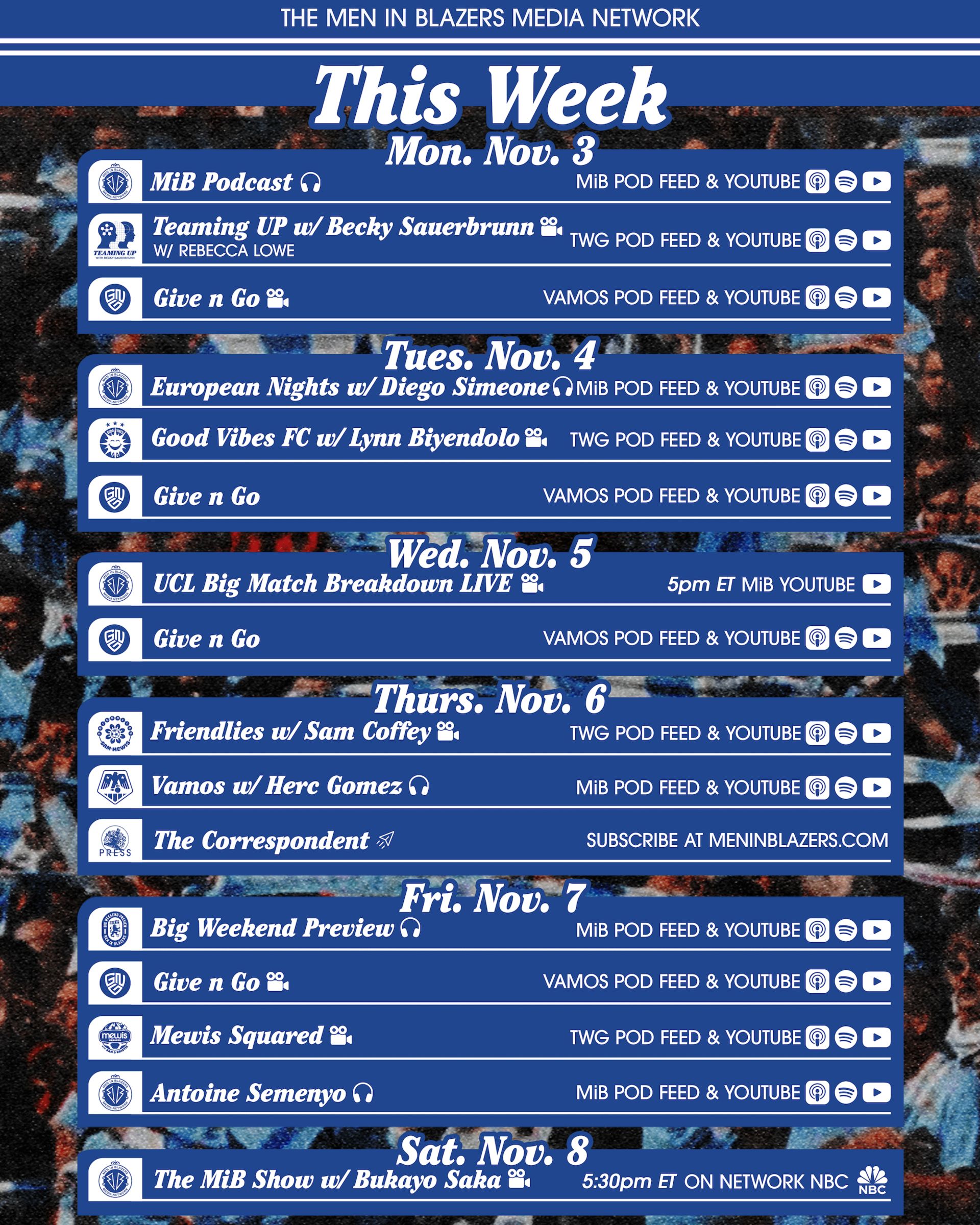

This Week on the MiB Pod 🎙️

Rog and Rory break down all the Premier League matches from last weekend, including another clean sheet and set-piece goal for Arsenal, Liverpool bouncing back as Slot reverts to old ways, and goal-scoring machine Erling Haaland continue to carry City into the title race. Plus, they discuss Tottenham's Jekyll and Hyde, home vs. away nature and ask if the English top flight is now more unpredictable than ever. Watch on YouTube or listen here.

Reading Material 💻

On tour in the heart of English football’s nostalgia industrial complex

My football group chats have this week mainly been about Mary Earps

My non-football group ones are more concerned with Lily Allen

Obviously podcasts are amazing but this is great

Life at Britain’s longest-running protest camp

Game of the Week 🔴💙

If anyone tuned in to Liverpool’s game with Aston Villa last week: my apologies. One for the purists, as they say. Or at least the emotionally invested. I think I’m on safer ground this week. Arsenal has had a poor start to its Women’s Super League campaign; lose to Sonia Bompastor’s all-conquering Chelsea early on Saturday and the domestic season is all but over. It’s only November, but it feels like a high-stakes sort of occasion.

📺 Watch on Saturday, 7 a.m. ET, ESPN

Correspondents Write In ✍️

A curiously heartening experience in the mailbox this week, as a surprising number of you railed against the absence of Sunderland in these newsletters. This is, you will not be shocked to learn, not something that happens very often. “We’re fourth in the Premier League, a staggering achievement for a promoted club,” wrote Bill Anderson. “I don’t expect it to last, but we must warrant a mention.”

You do, Bill, you do, although you should not really need me, a mere newsletter writer, to validate your emotions. As it happens, I’ll be at the Stadium of Light this weekend, for the visit/stroll to victory of Arsenal, and I’m expecting to find a considerably more buoyant club than the last time I was there, which was in the middle of some fruitless relegation battle several years ago.

I’d like to thank Andrew Laschober, too, for his particularly informative email. “Your Correspondent about the parity of the Premier League caught my attention, because it reminded me of West Coast USA collegiate football (the pointy-ball kind),” he wrote.

Now a lot of Andrew’s explanation of that parallel will be much more familiar to you than it was to me, so I will boil it down to this: the PAC-12 conference was killed by competitive balance.

All the teams tended to be of a similar standard – “Team A beat Team B, but Team B beat Team C and Team C beat Team A,” as Andrew put it – and so no team put up a particularly impressive record.

For reasons that might make sense to Americans but are completely baffling to me, this earned the conference the nickname “circle of suck.”

This was, it turns out, to the detriment of the conference. “TV deals started to be less well-funded than conferences that churned out one perennial powerhouse and sent them reliably to big-name bowl games,” Andrew wrote. “Eventually, the conference disbanded when a TV deal fell through. I don’t foresee that happening to the Premier League anytime soon, but it’s fascinating how parity can make for great fan experience, but lead to financial ruin as a whole. It’s wonderful to see Sunderland in the top 10. But I’m sure the money-men would prefer to see Liverpool and Man City in an unreachable two-horse race.”

That is, sadly, probably true. I’ve been thinking a lot about what an ideal Premier League would look like – maybe one for an international break there – but I’m pretty sure what fans would like and what the people who actually run the game might want would vary wildly. The big TV draws are the obvious ones: Manchester United, Arsenal and Liverpool, followed by Spurs, Chelsea, Manchester City and Newcastle. The broadcasters here tend to be happiest, I know, when those seven teams are all in Europe. And preferably on different nights…

That’s all for this week. Thanks, as ever, for reading. If you have an ideal Premier League to pitch, or any other quibbles or queries or questions for me, the address is [email protected]. We’d love to hear from you.

Take care,

Rory

Daily News for Curious Minds

Be the smartest person in the room by reading 1440! Dive into 1440, where 4 million Americans find their daily, fact-based news fix. We navigate through 100+ sources to deliver a comprehensive roundup from every corner of the internet – politics, global events, business, and culture, all in a quick, 5-minute newsletter. It's completely free and devoid of bias or political influence, ensuring you get the facts straight. Subscribe to 1440 today.