Greetings from Yorkshire!

January, certainly when experienced on a muddy, rain-sodden island just north of France, tends to drag. It is, apparently, still going on, despite it being wholly impossible to remember the start of it. Estimates would suggest that we still have three days of it to endure.

Weirdly, that temporal distortion has been made worse, rather than better, by the fact that January now contains a bottomless amount of football. It does not feel, for example, like it can be the case that Calum McFarlane experienced the high point of his managerial career – Chelsea’s 1-1 draw with Manchester City – in the exact same month that Michael Carrick single-handedly revived Manchester United in the space of 12 days.

The calendar is so packed, in fact, that it has actually managed to overshadow the transfer window. It has been unusually quiet, by the Premier League’s standards, admittedly; probably a necessary corrective after the excess of the summer. But there is one deal – not yet complete, as I write – that has struck a nerve with me; a transfer that’s a reminder of how fast time can move.

What Might Have Been 🤔

Timo Werner has nothing to regret, not really. Not by the standards of most of us: the humdrum, the normies, the civilians. He has, either at home or locked away in some bank vault, a Champions League winner’s medal, and a Europa League winner’s medal, as well as silverware from the European Super Cup and the German Cup and the (old) Club World Cup.

He has the memories of an elite career that has lasted more than 12 years, too. He has represented his country 57 times. He featured at a World Cup and a European Championship. He played in two of the most demanding leagues in the world, the Premier League and the Bundesliga, and at some of the planet’s most iconic stadiums. He graced one of Europe’s biggest sides, Chelsea, and spent time at three other sides from the game’s upper echelons: RB Leipzig, Stuttgart, Tottenham.

Timo Werner, in other words, has done OK. His story is not yet over – he has seemed on the verge of joining San Jose Earthquakes for most of the last month; at 29, he could well thrive in Major League Soccer – but however it plays out, wherever he ends up, it is not one that could sincerely be told as a tragedy. Timo Werner does not need to be pitied.

There is, though, just a tinge of sadness in the arc of his career, the path he has taken, the way it has worked out. No, not sadness. It is closer, maybe, to uncanniness, or unease, or incongruity: a ghost of a feeling of something missing, of a door unopened. Terry Pratchett, Britain’s finest ever author, wrote about the Trousers of Time. Every decision we take places us at the crotch, choosing whether to go left or right. It feels a little like Timo Werner went down the wrong leg.

It is not hard to identify his inflection point. In the spring of 2020, he was quite possibly the most coveted striker in Europe. He had just turned 24. He had spent the early years of his career breaking as many records as possible: Stuttgart’s youngest ever player, the youngest player to score two goals in a Bundesliga game, the youngest player to make 100, then 150, and finally 200 appearances in the Bundesliga. He was about to become the leading goalscorer in RB Leipzig’s admittedly brief history.

He was, very clearly, a star. He was not, it was true, the most reliable finisher; he tended to score goals in great hot streaks before running cold for a while, as though his calibration was off. But that was a tolerable flaw for a player cast in that Red Bull mold. He was a thoroughly modern centre forward: lightning quick, technically adroit and, maybe most importantly, an energetic and industrious pressing machine.

Everybody wanted him. Bayern Munich, as always, retained an interest in a domestic rival’s crown jewel. Chelsea, too, had been tracking his development, as had the rest of the Premier League’s moneyed elite. The widespread assumption, though, was that he would join Liverpool. His education made him – and the rest of the Leipzig school – a perfect pupil for Jürgen Klopp.

That move never materialized. There have been several explanations of why that might be, the most convincing of which is probably that Liverpool decided it could not justify the expenditure when the impact of the coronavirus pandemic was still unknown. Bayern did not move either, perhaps for the same reason. Chelsea, bankrolled by Roman Abramovich, was a little more willing to gamble.

It seemed as good a choice as any. Chelsea was, at that stage, in one of its periodic phases of trying on a new look. Werner was seen as one of a group of quick, young, inventive forwards, players who could play in a variety of different roles and a variety of different ways: Kai Havertz, Christian Pulisic, Hakim Ziyech and Mason Mount were his colleagues and competitors.

The season didn’t run quite as planned: when its young team hit a rough patch, Chelsea decided that the best course of action was to fire its manager, Frank Lampard, and replace him with Thomas Tuchel. Still, collectively, it worked: Chelsea won the Champions League at the end of that season. Werner started the final.

Individually, though, Werner never quite settled. Looking back, his numbers are not especially damning. In two full seasons at Chelsea, he scored 12 goals from 52 appearances in his first and then 11 from 37 in his second.

Admittedly, only 10 of those 22 came in the Premier League – the most important gauge for both fans and the broader commentariat – but still: it is hardly a shameful return, particularly given the change in manager, the age of much of the squad and the challenge of moving to a different country at the height of lockdown. There were mitigating circumstances.

That, obviously, did not matter in the slightest. Werner was doomed, really, from the first few months of his time in England, when he endured a spell of just one goal in 19 games. It was, he would later say, the “worst time in my career.” For most, it was enough to typecast him as profligate, unreliable, not a natural finisher. He was, from then on, always scrambling to regain his reputation.

In hindsight, it feels as though it is not too much of a stretch to say he never recovered. He returned to Leipzig in the summer of 2022, just another victim of the great BlueCo clear-out. He scored on his first game back; he was, it seemed, home again. He would, though, lose most of that season to an ankle injury; it would cost him a place at the World Cup, too.

A year later, he returned to England, joining Spurs on an initial loan; he did well enough at first that the club extended his stay for another season. That turned sour, too. At one point, Ange Postecoglou upbraided him publicly for a performance – in a Europa League game against Rangers – that was “unacceptable” for a “German international.” Tottenham elected not to make the move permanent, but Leipzig did not seem to want him back; the fact that he was the club’s highest-paid player was, perhaps, relevant to that. Werner has played only a minute this season; San Jose is his way out, his fresh start.

It would be overly indulgent to suggest he should not take any responsibility for his journey, of course. Oliver Mintzlaff, a long-serving executive within Red Bull’s sporting empire who now has a job title far too long and vacuous for me to type out, confesses to a “bias” towards Werner but has acknowledged that he is “certainly not an easy person, undoubtedly not an easy character” to manage.

“Every coach, whether Ralf Rangnick or Julian Nagelsmann, has had problems with him, but they’ve all played him,” he said last year. Quite what it is that makes Werner difficult he did not specify. Even allowing for that, though, his story has the quality of a warning, or a parable; it is a stark reminder of how delicate a career football can be.

We will never know, of course, what might have happened had Werner signed for Liverpool or Bayern or even stayed at Leipzig that summer. It is only with hindsight that we can say Chelsea was the wrong move; when Werner made his choice, there would have been plenty of perfectly legitimate reasons to feel Stamford Bridge was the right call. “I decided for Chelsea not only for the style of football, but also what they have shown me,” he said, a few months into his stay. “It feels right.”

That feeling, though, was an illusion. Werner got a single, impossible decision wrong – no, not wrong, just not right – and everything unspooled from there. He does not warrant pity; he has had a career that the vast majority of other professionals would envy. And yet it is still, perhaps, not the career he should have had, or that he might have had, or that he seemed destined to have.

That comes at a personal cost: much of the reporting of his move to the United States has focused on Werner’s desire to rediscover his love for football, for what he does. It is not hard to see why he might have lost sight of that, over the years, or to understand why he might think it is now time to see if he can unearth it again, far from home.

📬 Enjoying The Correspondent? Check Out Our Other MiB Newsletters:

🐦⬛ The Raven: Our Monday and Friday newsletter where we preview the biggest matches around the world (and tell you where/how to watch them) and recap our favorite football moments from the weekend.

☀️ The Women’s Game: Everything you need to know about women’s soccer, sent straight to your inbox each week.

🇺🇸 USMNT Only: Your regular update on the most important topics in the U.S. men’s game, all leading up to this year’s World Cup.

Europe’s Premier League 🏆

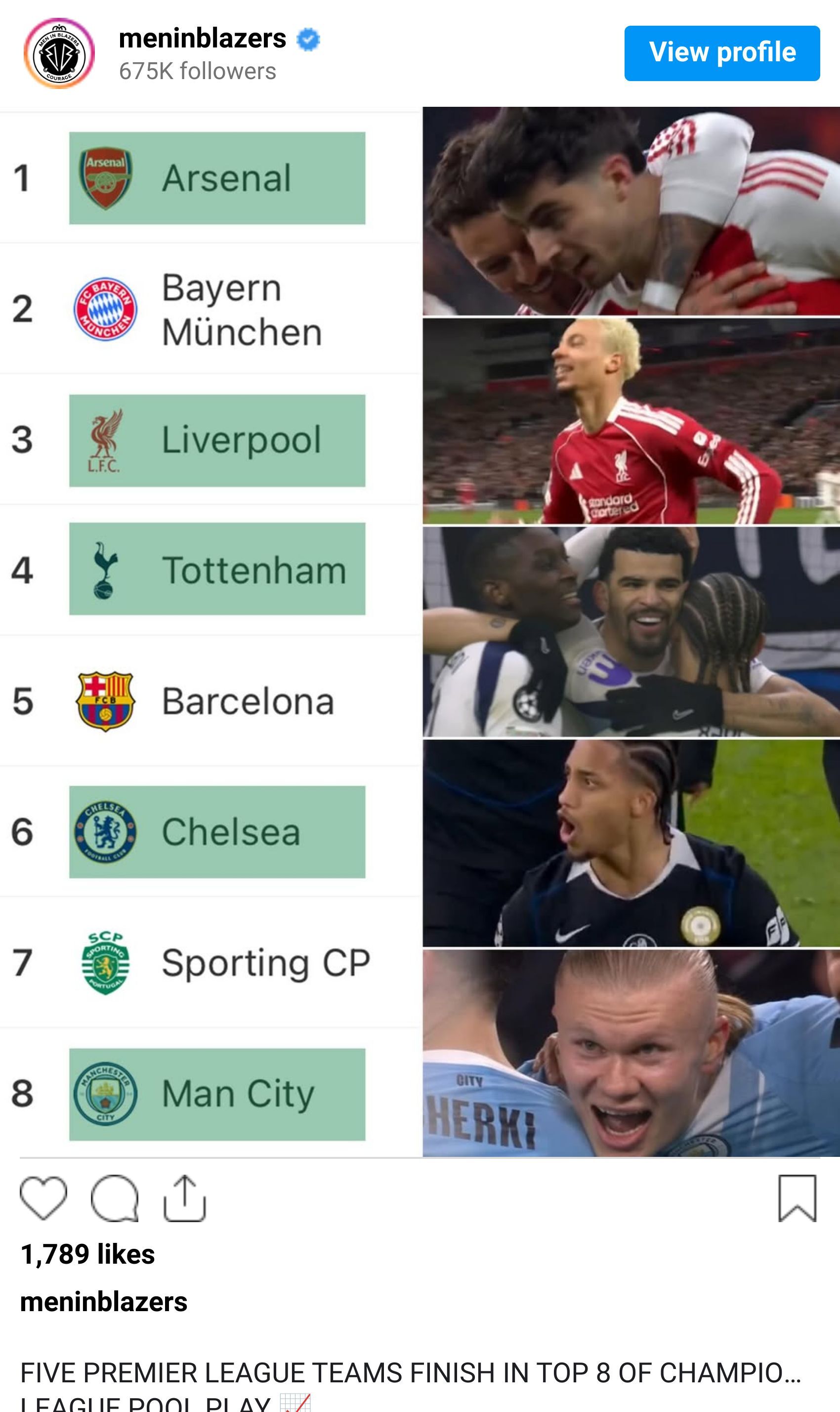

One glimpse at the extendable table of the Champions League’s group phase is enough to confirm something we all knew: England’s clubs now exert a dominance on European football that is essentially unprecedented. There are six Premier League teams in the world’s elite club competition. Five of them finished in the top eight.

The one that didn’t, Newcastle, missed out because Eddie Howe’s team only managed to draw with Paris St-Germain. That setback should only be temporary: Newcastle will expect to get past either Monaco or Qarabağ in the playoff round. It is overwhelmingly likely that six of the last 16 will be English. As The Athletic’s Adam Crafton pointed out: if Aston Villa and Manchester United were in the competition, they would probably have made it, too.

This is fairly obviously bad for the Champions League, which increasingly resembles a sort of sideshow to the Premier League. It is also demonstrably bad for the health of the European game as a whole, which would work a lot better in both a sporting and an economic sense if there was more of a counterweight.

But it might, oddly, also be bad for the Premier League. Given England’s financial advantages, it is strange that only three of its sides – Liverpool in 2019, Chelsea in 2021 and Manchester City in 2023 – have won the Champions League in the last 13 years. There have been four runners-up in the same timeframe; England has provided, in other words, just seven of the 26 finalists.

Given the vast difference in wealth, that is an underperformance, and it is one that has to be rooted in the league’s strength in depth. Many of Europe’s best teams are clustered in England. That makes the domestic season impossibly taxing. They look imperious in January. By May, the cumulative fatigue has set in; they are, in effect, punching each other out.

This Week on the MiB Pod 🎙️

Rog and Rory break down Arsenal’s dramatic 3–2 loss to Manchester United at the Emirates, analyzing why questions are growing around Arsenal’s mentality in the Premier League title race. The pair also discuss Michael Carrick’s immediate impact at Manchester United and how he’s transformed the team so quickly. Plus, they recap all the key moments from Premier League Matchweek 23, including Chelsea’s win over Crystal Palace, Bournemouth’s last-minute victory against Liverpool, and what’s currently not clicking for Arne Slot’s Liverpool.

Reading Material 📚

Is football’s final form incredibly rich teams hurling throw-ins at each other?

The unfurling tragedy of Welsh rugby (sad even though it is rugby).

The people who email are better than the people who comment.

On Minnesota.

The story of an ice-skating trailblazer who is not remembered nearly enough.

The Watchlist 📺

There is a tab open on my laptop at all times where I note down all the things that I think could one day be stories. Some are people I want to interview. Some are concrete ideas about specific clubs, or themes, or places. Some are vague thoughts that have stayed with me for long enough for me to write them down. I will get around, at best, to doing about a quarter of them.

The words “The Friendly Derby” have been sitting on that list for… well, for some time. I’m fascinated by the relationship between Athletic Club and Real Sociedad, the twin poles of Basque football, who face each other on Sunday. (With all due respect to Eibar, Alavés and sort of Osasuna.)

They are, as you would expect, fierce rivals: one representing the economic might of Bilbao, the other the more genteel surrounds of San Sebastian. And, likewise, their games tend to be intense and frantic and occasionally fiery.

But what makes them unique, I think, is that none of that is reflected in the stands. The atmosphere is loud and raucous and defiant but it is also friendly; fans mix both inside and outside their respective stadiums. It sits at odds with one of the sport’s received wisdoms, which is that you need tribal hostility to create fervor. One of these days, I’ll manage to organize myself enough to go and find out why.

Correspondents Write In ✍️

An avoidable and regrettable mistake from reader Gareth Pearce, who made the fateful error of inviting me to talk about my two favorite subjects: the football media, and myself. “I’ve noticed in recent years that you’ve become more forthcoming about the fact that you’re a Liverpool supporter,” he wrote, acknowledging that he suffers from much the same affliction.

“Was ‘coming out’ as a Red an intentional move on your part, or just something that happened over time? Given the fact that Jamie Carragher and Gary Neville et al wear their club affiliations very much on their sleeve, does it say something about the football media landscape that journalists are doing likewise, or is it a move towards more increased authenticity?”

I’ll do my best to keep this self-indulgence relatively brief, Gareth: it’s a bit of all three. I was taught, as a journalist, that nobody should know the color of your team or of your politics, and I think that’s still good advice. Such good advice, actually, that the world might be quite a lot happier if more people adhered to it.

But I’ve also worked for American organizations for a long time; supporting a team does not carry quite the same connotations there as it can in England. There were more occasions when it felt OK to admit it because it did lend that authenticity. Obviously, once something is in the public domain then there’s very little point trying to deny it.

That said, it has its drawbacks: a section of any given audience assumes that any opinion I might have must necessarily be rooted in my fandom; it makes it too easy, I think, not to engage with the actual idea. And I’m still uneasy about pundits, people far more important in forming the game’s discourse than me, being quite so partisan. Fans might see neutrality as a pretense, but some pretenses – good manners, for example – exist for a reason.

I’ll stop there, or I’ll end up writing a whole other newsletter, and nobody needs that. I’ll be at Elland Road on Saturday to see Arsenal render an entire week of debate completely irrelevant, and then I’ll be back home in time to watch through my fingers as Liverpool crumbles at home to Newcastle. I hope you enjoy your weekend more than I will!

Take care,

Rory

As always, you can send any questions, thoughts, or odes to Terry’s Chocolate Oranges to [email protected].

If you’re enjoying The Correspondent, we’d love an assist. Forward this email or share this URL with a friend, family member, or fellow football fan.

First time with us? Sign up here to get Rory’s next newsletter sent straight to your inbox.

Seeking impartial news? Meet 1440.

Every day, 3.5 million readers turn to 1440 for their factual news. We sift through 100+ sources to bring you a complete summary of politics, global events, business, and culture, all in a brief 5-minute email. Enjoy an impartial news experience.